“It is a precarious enterprise, and only a fool would try to compress a hundred centuries into a hundred pages of hazardous conclusions. We proceed.” – Will Durant, The Lessons of History

It is easy to believe to study history is simple – that when we open any book on the subject, we are reading the objective relaying of a collection of facts that an author utilized to present clear-cut examples of cause and effect; the reader need not be so critical, he is merely an audience absorbing truth. But in The Age of Faith, Will Durant wrote that “The historian always oversimplifies, and hastily selects a manageable minority of facts and faces out of a crowd of souls and events whose multitudinous complexity he can never quite embrace or comprehend.” In the face of this difficulty, what lessons are there to truly learn from history? What wisdom can be gained honestly from its study – that is, not merely sought out to confirm an existing bias? In Lessons of History, Will and Ariel Durant reflect on a lifetime spent as two of history’s most diligent scholars, sharing their great gift of perspective.

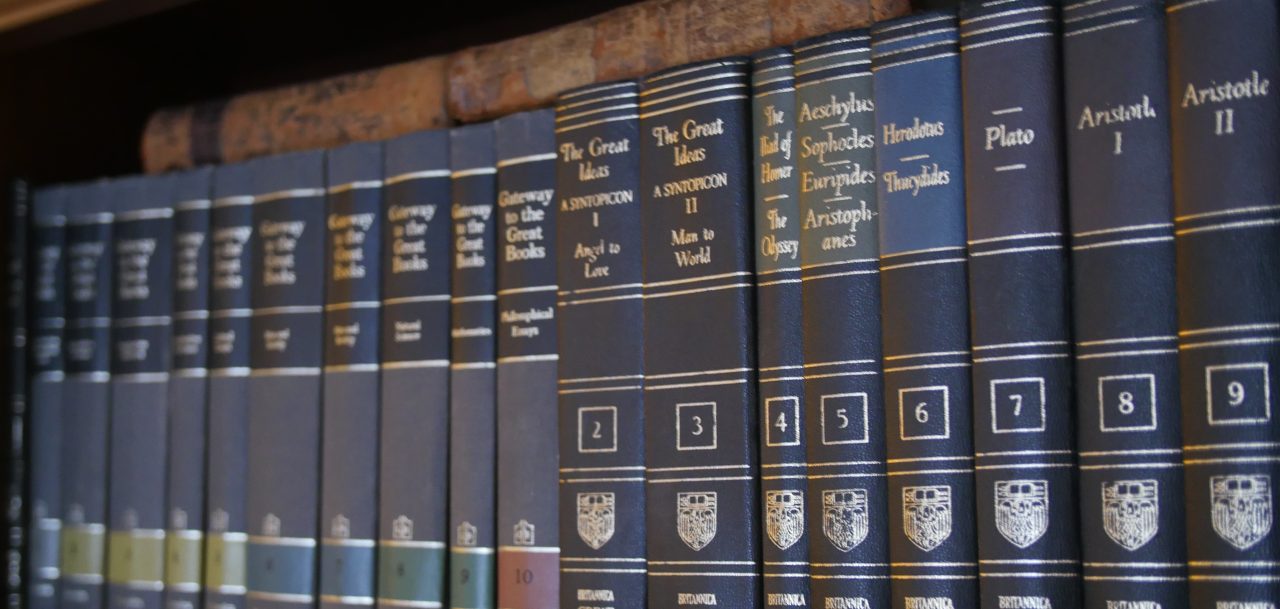

Lessons of History was first published in 1968. This book, along with Interpretations of Life, was published before the Durants would move on to publish their eleventh and final Story of Civilization: The Age of Napoleon. The book itself is divided into thirteen chapters, wherein the authors discuss the insights the study of history has to offer on biology, race, character, morals, government and more.

While rereading and revising their ten volumes of The Story of Civilization, Will and Ariel Durant “made note of events and comments that might illuminate present affairs, future probabilities, the nature of man, and the conduct of states.” This book is the result of that survey. It opens with Hesitations, a chapter defined by the couple’s characteristic humility, with the authors asking: “Of what use have your studies been?” Much of the book is spent adding perspective to studying itself of history: “Our knowledge of any past event is always incomplete, probably inaccurate, beclouded by ambivalent evidence and biased historians, and perhaps distorted by our own patriotic or religious partisanship… Even the historian who thinks to rise above partiality for his country, race, creed or class betrays his secret predilection in his choice of materials, and in the nuances of his adjectives.” They quote their own words from The Age of Reason Begins, writing: “History smiles at all attempts to force its flow into theoretical patterns or logical grooves; it plays havoc with our generalizations, breaks all our rules; history is baroque.”

The lessons throughout it are insightful, clever and substantial. In History and the Earth, the Durants describe the immense influence geography and climate had on the development of civilizations past but observe that “the development of geographic factors diminishes as technology grows” – that is, with the modern technological revolution and the rise of the airplane, we are living in an unprecedented era.

In Biology and History, they comment on the ‘survival of the fittest’: “…the laws of biology are the fundamental lessons of history. We are subject to the processes and trials of evolution, to the struggle for existence and the survival of the fittest to survive. If some of us seem to escape the strife or the trials it is because our group protects us, but that group itself must meet the tests of survival.” Much of the chapter is spent discussing the timeless and unending strife between freedom and equality: “Since Nature (here meaning total reality and its processes) has not read very carefully the American Declaration of Independence or the French Revolutionary Declaration of the Rights of Man, we are all born unfree and unequal… Nature smiles at the union of freedom and equality in our utopias. For freedom and equality are sworn and everlasting enemies, and when one prevails the other dies.” Other points in this chapter mirror themes he covers in his Pleasures of Philosophy, and he expands upon them here: “Inequality is not only natural and inborn; it grows with the complexity of civilization. Hereditary inequalities breed social and artificial inequalities; every invention or discovery is made or seized by the exceptional individual, and makes the strong stronger, the weak relatively weaker, than before. Economic development specializes functions, differentiates abilities, and makes men unequally valuable to their group.”

In Character and History, The Durants describe the dialectical forces that continually shape history: “Out of every hundred new ideas ninety-nine or more will probably be inferior to the traditional responses which they propose to replace. No one man, however brilliant or well-informed, can come in one lifetime to such fullness of understanding as to safely judge and dismiss the customs or institutions of his society, for these are the wisdom of generations after centuries of experiment in the laboratory of history.” Continuing later in the chapter, they state: “It is good that the old should resist the young, and that the young should prod the old; out of this tension, as out of the strife of the sexes and the classes, comes a creative tensile strength, a stimulated development, a secret and basic unity and movement of the whole.”

It is a short work at a mere hundred pages, and it is easy to wish for the book to be longer so that we might squeeze as much insight as we can from the Durants – but in doing so we would defy the nature of the book and its intentions. This book largely succeeds in Nietzsche’s goal of saying in a few sentences what it takes others a book to say – for to find ourselves wanting an expansion of observation or supply of additional evidence is to miss the point. It is their Story of Civilization that serves as evidence and argument. These are authentic observations, not theses supplied with immediate proofs. After such a tireless work as the prior volumes, they have earned the right to make these brief reflections.

The authors conclude with remarking again on the difficulties of the book’s endeavor: “History is so indifferently rich that a case for almost any conclusion from it can be made by a selection of instances.” It is human nature to crave easy conviction – to seek out edicts whereby we may consider ourselves morally exceptional or generally superior to those who have not subscribed to our principle of the moment. The existential discomfort of living provokes us to seek some cornerstone upon which we tell ourselves: “I may not know what I’m doing, but at least I am better than those who are not like me.” The Durants do not humor this all-too-human frailty, and for that their work is all the more crucial to wisdom, empathy and understanding.