“To put an end to the spirit of inquiry it is not necessary to burn the books. All we have to do is leave them unread for a few generations.” – Robert Hutchins, The Great Conversation

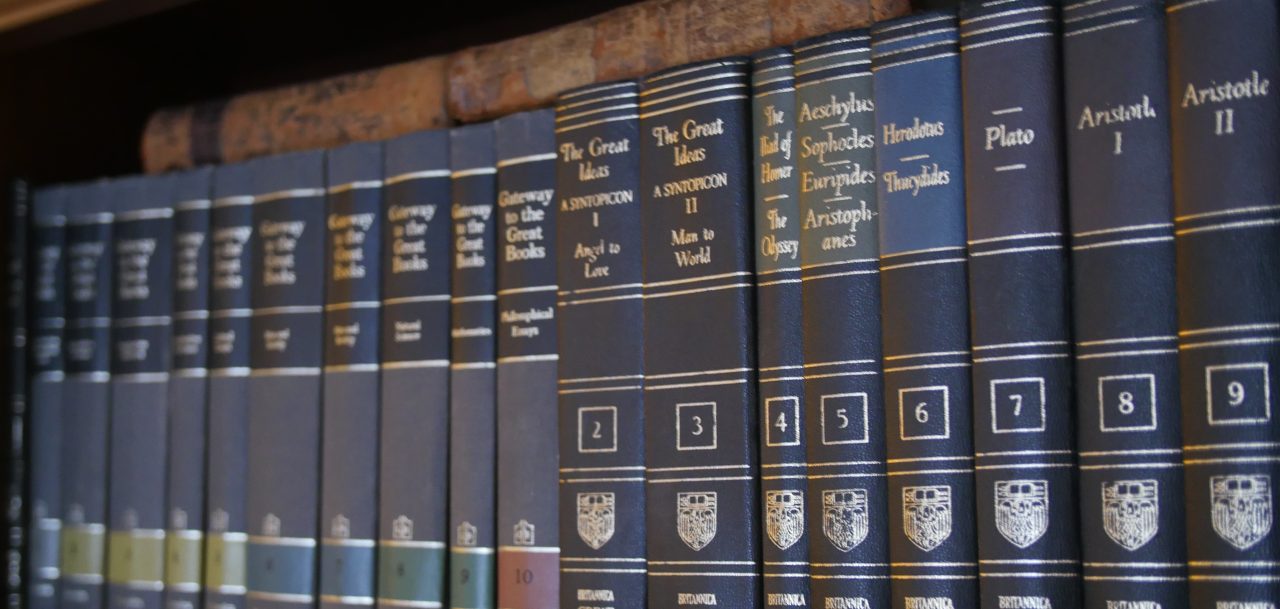

The shortest and surest road to wisdom is to understand it by its near synonym – perspective. Wisdom is to see beyond fad and fashion – beyond modern, postmodern; wisdom is historical. If you desire wisdom, and thereby perspective, you must necessarily join the Great Conversation. Perfectly titled, The Great Conversation is Encyclopedia Britannica’s introduction to the company’s ‘Great Books of the Western World’ set. Written by Robert Hutchins, the Editor-in-Chief of Encyclopedia Britannica at the time of publication in 1952, it serves as ‘Book One’ of the set and – despite some awkward decisions, it nevertheless serves as an excellent invitation to the definitive history of Western intellectual thought.

The overarching theme of the book stems from the title itself as it refers to what the set of books is intended to be – humanity’s shared progress in understanding life seen through the lens of a conversation; that is, progressive books in the set appear to know of, converse, debate, and build off those that came before. This conversation is the story of Western intellectual history.

The book is comprised of ten chapters, each seeking to emphasize the importance of The Great Books of the Western World set through a different point and argument. It provides an excellent perspective for the reading of classics through these different approaches – that education should be considered a life-long journey, that this sort of liberal education is on its decline – and so on. Its chapters largely seek the same goal overall – but there is a considerable overlap of points. The overall thesis is to persuade the reader of the value of these books and to convince you to continue reading further into the set. So too do they want it understood that these works are timeless – and the editors do not see themselves as mere “…tourists on a visit to ancient ruins or to the quaint productions of primitive peoples.”

Hutchins too addresses common concerns about the reading of classics. Many were written when men held slaves. Some pre-date the scientific method. How can they possibly be applied to our current society? Hutchins calls the dismissal of the timelessness of these works a kind of “sociological determinism.” That is, the books are not meant for one age alone. Hutchins’ childhood dreams were to become an “iceman” or a “motorman” – occupations dying in his era, completely extinct in ours. He argues – “No society so determines intellectual activity that there can be no major intellectual disagreements in it. The conservative and the radical, the practical man and the theoretician, the idealist and the realist will be found in every society…” – and so too are they found in this set.

I do wish more of the book followed the theme of the preface, explaining more of the methodology and overall process in creating the set as opposed to the ‘preaching to the choir’ sentiment other chapters of the book assume – but a middle chapter, titled ‘Experimental Science,’ is an interesting pinnacle of the book. We naturally grateful for the efforts of Ptolemy, of Kepler, of Gilbert and Huygens – but it is a common question to ask – what use are they to me now? Is it not a better use of my time to simply read the most modern textbook as opposed to these dated works riddled with antiquated knowledge? This is the perspective the editors seek to correct: “…[we] do not agree that the great poets of every time are to be walked with and talked with, but not those who brought deep insight into the mystery of number and magnitude or the natural phenomena they observed around them.” Reading the works of these ancients is not necessarily about learning what is true – it is about conversing with one of history’s greatest minds while it thinks as clearly as possible with the facts it has at its disposal. It is this precision of thought and language that makes the reading of these works worthwhile: “As far as the medium of communication is concerned, they [scientific books] are products of the most elegant literary style, saying precisely what is meant.” In our age, it is not hard to see how many treat science as a kind of faith – ignoring the scientific method and accepting whatever pleases them if it affirms a pre-existing bias. This is another reason why these works are so valuable, so Hutchins states: “The facts are indispensable; they are not sufficient. To solve a problem it is necessary to think. It is necessary to think even to decide what facts to collect… Those who have condemned thinkers who have insisted on the importance of ideas have often overlooked the equal insistence of these writers on obtaining the facts. These critics have themselves frequently misunderstood the scientific method and have confused it with the mindless accumulation of data.”

The editors are well-enough aware of how “intimidating” the set of books can feel. The authors and their texts are not condensed or edited – and being presented with the totality of such monumental works can feel insurmountable to understand. But Hutchins counters this sentiment perfectly – “The question for you is only whether you can ever understand these books well enough to participate in the Great Conversation, not whether you can understand them well enough to end it.” And it is this sentiment of uneasiness of being able to feel as though you conclusively ‘finished’ a Great book, understanding it in its totality, that the author wants you to see cannot be done and should not be your goal: “There is a simple test of this. Take any great book that you read in school or college and have not read since. Read it again. Your impression that you understood it will at once be corrected. Think what it means, for instance, to read Macbeth at sixteen in contrast to reading it at thirty-five… To read great books, if we read them at all, in childhood and youth and never read them again is never to understand them.”

My issue with the work largely rests with the book’s ambiguity of purpose and the extent it seems to pamper anyone pre-emptively in agreement. The final chapter, ‘A Letter to the Reader,’ opens thus: “I imagine you are reading this far in this set of books for the purpose of discovering whether you should read further… The Editors are not interesting in general propositions about the desirability of reading the books; they want them read. They did not produce them as furniture for public or private libraries.” The point is noble enough, but it is again attempting to convince those who would never read this collection of works– and thereby has immediately dated itself, betraying a lack of perspective. Who would go out of their way to purchase ‘The Great Conversation’ alone? Yes, there are many who would purchase the set for an unearned appearance of worldliness, but was it worth partly framing the work with them a target audience? What of the rest who jumped in, to phrase it rather arrogantly, with caution to the wind? I can appreciate this catch-all approach to formulating a theme, but such passages can make the book feel over-long, even at a very modest 82 pages. If you are in early agreement with the of majority of the author’s points, you would quickly become suspicious at the degree to which you are being catered to.

Lovers of great books will likely hold Hutchins’ posed truths to be self-evident. Being so ardently coddled would put any decent mind on guard – and cause it to ask what it is being sold. And yet, Hutchins nevertheless presents one of the rarest encounters – where there is no snake oil – and the author is genuinely handing you the keys to the universe. One only wishes they were dealing with a better salesman. In spite of these flaws, I would argue it a worthy read independent of the context of the set of books. More than anything, its intention is to “arm” the reader – to go out and be strong advocates for the reading of great books. It is a work born out of a sense of mourning, and if Hutchins was dismal about the state of liberal education over half a century ago, one could only imagine what he would feel today. Yet my estimation of the faults is likely hyperbolic. Did the editors rise to the occasion of making a satisfying introduction to the set? Yes, but with clauses. Could they have done more? Absolutely. Are their causes one of the most important and noblest in the world? Unequivocally.